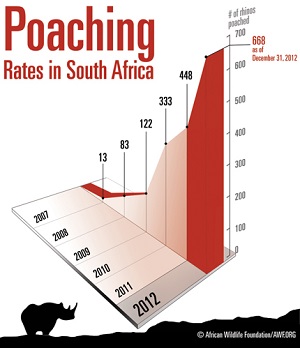

Rhino horn is now more expensive (by weight) than gold or cocaine and as a result rhino poaching is reaching epidemic proportions. The number of rhino’s lost to poaching in South Africa climbed from 300 in 2010 to 668 in 2012! 232 rhinos have already been killed in 2013. And these numbers only represent South Africa! Rhino poaching is on the rise in East Africa as well.

There has been a lot of recent coverage of the increase in poaching of both rhinos and elephants (from the BBC to the New York Times to National Geographic) but as far as I’m concerned there can’t be too much attention on this issue, so here’s my contribution.

Today I want to talk about the Rhino Rescue Project (RRP), which is spear-heading a new and unique effort to prevent poaching in reserves around Kruger National Park in South Africa.

The idea is essentially to poison the horn to eliminate the its value

In addition to its ornamental value, much of the rhino horn that is sold illegally is consumed. RRP realized that if they could make the horn indigestible it would decrease the demand, so they decided to infuse into the wild rhino horns the same ectoparasiticide used to control ecto-parasites like ticks in captive rhinos, effectively making the horn toxic.

After some additional research and consultation they decided to add an indelible dye to the infusion, similar to products used in the banking industry to prevent counterfeiting. The dye is visible on an x-ray scanner even when ground to a fine powder so airport security checkpoints can pick up the presence of a treated horn whether the horn is intact or in powder form.

The combination of the dye and the ecoparasiticides are intended to destroy the monetary value of the horn and discourage poaching with little to no impact on the rhino. Comprehensive testing is ongoing to ensure that the animals have not been harmed by the treatment. The acaracide selected is even one that is “Ox Pecker-friendly” (a bird commonly found “pecking” rhinos looking for ticks) to ensure little or no damage to other animals and organisms sharing the rhino’s habitat. It is expected that the treatment will remain effective for three to four years before re-administration is required. In addition to the treatment and dye, a DNA sample is collected and added to a national database to aid in prosecutions of poachers.

The first large scale horn infusions recently began in the Sabi Sand Reserve, west of Kruger National Park. Over 100 rhino have been treated and there have been zero losses.

There has been speculation and some outcry that the program’s aim is to poison rhino horn consumers.

In RRP’s efforts to clarify their position they have pointed out that; 1) the ecoparasiticides are toxic but not lethal to humans and 2) central to the program’s success is the extensive publicity surrounding the effort.

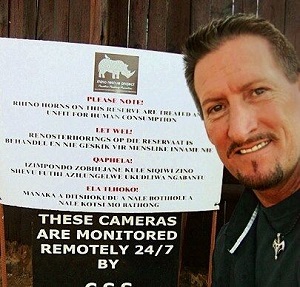

If the rhinos in a given reserve have been treated, it is widely publicized with 200+ signposts around the reserve’s perimeter and, if a treated rhino is killed, the indelible dye is clearly visible inside the horn to indicate that the horn had been tampered with. RRP also strongly advocates involving as many reserve staff as possible in the horn treatment process so that word about the treatment spreads. All of properties and reserves in the Sabi Sands who have participated in the program are also posting extensively on social media.

RRP’s hope is that the publicity prevents the rhino’s being poached in the first place and that treated rhino’s will be left alone, their horns intact. From RRP’s perspective every treated horn that enters the market means another rhino has died and the program has failed that animal.

This effort really interested me not only because it involves close cooperation with many of the properties I work with, but also because it is an innovative and proactive solution to rhino poaching that is cost-effective for reserves with small rhino populations that do not have the resources to provide each rhino with an armed guard.

Other Anti-Poaching Efforts

This is by no means the only approach to preventing rhino poaching going on in Africa. Other tactics include traditional methods like 24/7 armed guards and rhino relocation (for example from the Solio and Lewa Conservancies in Kenya and Phinda Private Game Reserve in South Africa) to more innovative tactics such as the horn infusion described above and East Africa’s first unmanned drone patrolling Kenya’s Ol Pejeta Conservancy.

There is also an on-going debate over the creation of a legal market for horn harvested from farmed rhino. Because rhino horn is made of compressed keratin (similar to fingernails and human hair) it can be trimmed periodically. Each rhino can produce about a kilo of horn per year and supporters argue that harvested horn could increase volume enough to drive down the price of illegal horns and reduce poaching. They point to the legal trade in farmed crocodile skins as an example of how legal trade can drive conservation.

Opponents argue the harvest procedure is invasive and harmful to the rhino and that the trade is driven by excessive demand not lack of supply and that a legal trade would not discourage poaching. They point to examples including ivory and abalone where criminal markets flourish alongside the legal one and encourage poaching. Mary Rice, executive director of the Environmental Investigation Agency points to the spike in illegal ivory sales in China after it legally bought stockpiles of ivory from Botswana, South Africa, Namibia and Zimbabwe in 2008. (Find more about the farming debate here)

Whatever the end result of the debate, a variety of solutions clearly need to be explored because if the pace of poaching continues to accelerate, Africa’s rhino could be extinct in the wild in just 20 years! Some species including the Western Black Rhino are already gone.